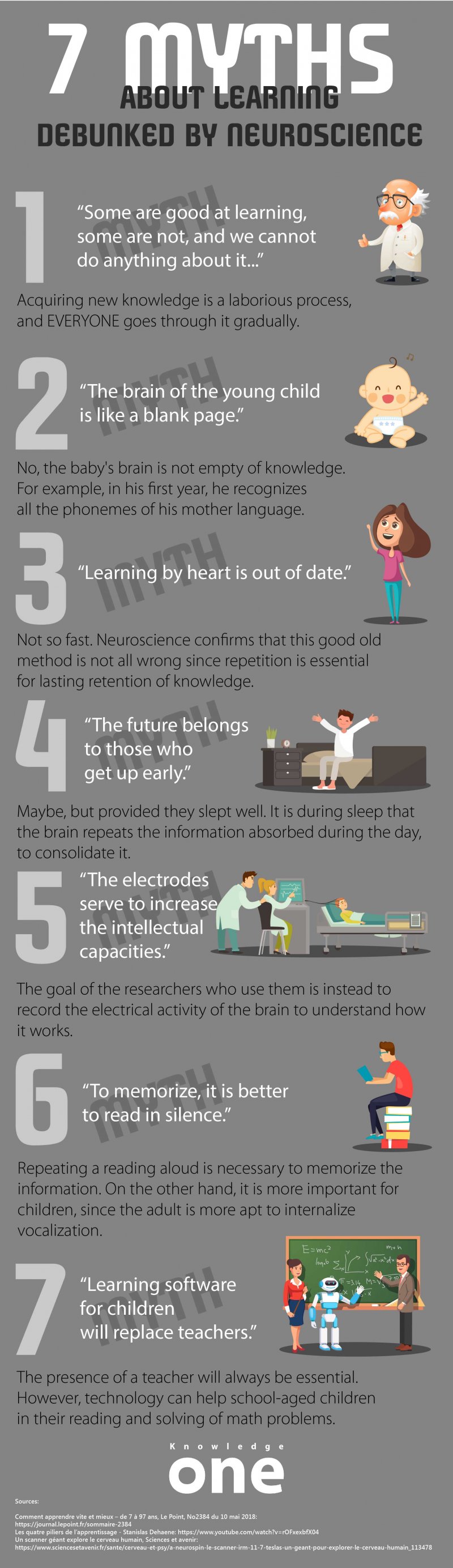

Neuroscience has shed new light on how our brain learns. Although much remains to be explored, we now know that some beliefs may be left behind, while others deserve renewed interest. Here are 7 myths passed through the filters of neuroscience:

-

Some are good at learning, some are not, and we cannot do anything about it…

Here is a belief better to be forgotten as quickly as possible. Acquiring new knowledge is a laborious process, and EVERYONE goes through it gradually. Sometimes it is enough to approach learning from a playful angle to stimulate our curiosity sufficiently and to develop unsuspected benefits. In preschool children, word games and nursery rhymes, in addition to being amusing, can prepare them “seriously” for reading.

For both young and old, learning to play a musical instrument stimulates the development of many parts of the brain and provides long-term benefits. Regular sport or learning a new language helps to slow down cognitive decline and preserve memory. In addition, since the brain is endowed with certain plasticity, learning – with its benefits – is possible at any age.

-

The brain of the young child is like a “blank page”

No, the baby’s brain is not empty of knowledge … As proof, the baby already has a sense of numbers: he can evaluate the quantities intuitively, knowing how to make the difference for example between 2 objects or a dozen. During his first year, the child already recognizes all the phonemes of his mother language.

In short, the little human being has an excellent “learning algorithm,” which means that around 3 years old, he can associate objects with symbols – especially numbers – and thus begins to do mathematics. As for language circuits, they are set up from 2 months and are well established at 5 years.

-

The learning by heart is out of date

Not so fast. In fact, neuroscience confirms rather that this good old method is not all wrong! Repetition is a prerequisite for the retention of knowledge. To achieve optimal results, however, the distribution must follow a principle: study in a concentrated manner over short periods, at spaced intervals.

It is this form of training – the so-called “distributed” learning – that gradually intertwines connections for new knowledge to shift from working (or short-term) memory to long-term memory. Once a learning process is automated, the brain is free to move on to the next one.

-

The future belongs to those who get up early

Maybe, but provided they slept well. This is because, throughout sleep, the brain replays the information absorbed during the day. The region of the hippocampus, which plays a fundamental role in episodic memory and the consolidation of learning, is then very active.

We do not know precisely how sleep intervenes. It could be by allowing a clean-up that would restore to its best the faculty of learning or the translation into rules of the day-to-day episodic information. Nevertheless, 10 hours of sleep are recommended for children, and between 7 and 8 hours for adults.

-

The use of electrodes in neuroscience research aims to increase intellectual abilities

It’s not so much a myth about learning as it is about neuroscience … but this odd-yet common-idea needs to be clarified. The goal of researchers is to record the electrical activity of the brain to understand how it works.

Neuroscientists use other types of devices, including those with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) that can visualize soft tissue to map the functional activities of the brain. A highly anticipated fMRI will be operational in France in 2019 at the NeuroSpin Center. It will produce 100 times more accurate images than we have now.

-

To memorize, it is better to read “in your head”

Repeating the reading aloud is necessary to memorize the information. This exercise is, however, more critical for children, since as we get older, we become more apt to internalize vocalization, in other words, to read in our head.

In addition to helping to record information, vocalization and self-repetition serve as auxiliary memory in mental arithmetic or for understanding longer sentences (Baddeley, 1992).

-

Learning software for children will replace teachers

The presence of a teacher will always be essential. However, well-developed, technology can help school-aged children in their reading and solving of math problems. Since it takes thousands of repetitions to decode a word at this age, software designed by neuroscientists allows the child to train at specific tasks, at his own pace, according to his level and in a fun way.

Remember that the effects of screens on the brains of young people are of concern to public health authorities, who have made recommendations to this effect (Naître et grandir). It is therefore recommended for children not to spend hours, every day, in front of a screen, even for educational purposes. It would not be necessary either. For example, researchers have estimated that using GraphoLearn software for 15 minutes a day, 4 days a week, gave students a 16 hours advance per year in decoding texts. The first serious games of this type were designed by Finns in the early 2000s to treat dyslexia.